|

| Torâh | Haphtârâh | Âmar Ribi Yᵊhoshua | Mᵊnorat ha-Maor |

|---|---|---|---|

2006.03.17 300x136.jpg) |

In the entirety of the universe, why is Tor•âhꞋ right? Why aren't other religions also right?

These are oft-asked questions, especially by young, college-age, adults. Knowing how to answer these questions is essential.

The most ancient record of man communicating with the other world, the spirit(ual) world of the divine, is the Biblical account of Mosh•ëhꞋ at Har Sin•aiꞋ. The Biblical account is then replete with instantiations of successors to Mosh•ëhꞋ, who followed his prescription, and similarly communicated with the Singularity-Creator; like Eil•i•yâhꞋu ha-Nâ•viꞋ.

|

| Beit-ha-Tᵊphutz•otꞋ Museum, Teil •vivꞋ University campus |

Where is there a reliable record of anyone, outside of these Biblical personalities—and RibꞋi Yᵊho•shuꞋa who also followed his formula—who has demonstrated like success in communicating with the spiritual realm of the Creator?

Who, today, can demonstrate this level of communication with the spiritual realm of the Almighty?

This is why Tor•âhꞋ is right, because [a] it's the only proven formula for a communications portal to the incorporeal realm of the Singularity and [b] because a perfect Singularity implies a perfect formula (only) to commune with Him. Therefore, no other formula (i.e., religion) can be right.

normal matter (rd) visible (bw) 200x200.jpg) |

Concerning other religions, plainly stated: their way don't work! They're wrong and false, misleading people astray.

Clearly, to communicate with the Singularity requires that we learn the formula handed down to Mosh•ëhꞋ at Har Sin•aiꞋ. How do we do that? Bâ•rukhꞋ é--ä, Mosh•ëhꞋ developed reiterative symbolism and liturgy encrypting repeated clues for those initiated in Tor•âhꞋ, which éÄùÒÀøÈàÅì—specifically the Teimân•imꞋ—has painstakingly preserved from the time of Mosh•ëhꞋ until today.

Mosh•ëhꞋ's derivation of this formula and his encryption of the formula in these symbols are the major subject of my book, The Mirrored Sphinxes Live-LinkT ![]() . Remember that, to commune successfully with the Singularity, éÄùÒÀøÈàÅì is commanded to differentiate between the ÷ÉãÆùÑ and the çÉì (wa-Yi•qᵊr•âꞋ 10.10; Yᵊkhëz•qeilꞋ 22.26; 44.23). Every symbol indicates three essential gradations. Paralleling these gradations is informative. It isn't feasible to duplicate here what will be in my book, but I'll provide a table that enables you to ponder the basic relationships, which The Mirrored Sphinxes Live-LinkT

. Remember that, to commune successfully with the Singularity, éÄùÒÀøÈàÅì is commanded to differentiate between the ÷ÉãÆùÑ and the çÉì (wa-Yi•qᵊr•âꞋ 10.10; Yᵊkhëz•qeilꞋ 22.26; 44.23). Every symbol indicates three essential gradations. Paralleling these gradations is informative. It isn't feasible to duplicate here what will be in my book, but I'll provide a table that enables you to ponder the basic relationships, which The Mirrored Sphinxes Live-LinkT ![]() explains in more depth.

explains in more depth.

| Gradation | Outer | Middle | Inner |

|---|---|---|---|

| àøåï äòãåú | left wingtip-to-wingtip contact | right wingtip-to-wingtip contact | face-to-face (contact & communication) |

| îùëï & Beit-ha-Mi•qᵊdâshꞋ | Enter: àåÌìÈí, surrounded by stones = ðÀôÈùÑåÉú | äÅéëÈì / Beit-ha-Mi•qᵊdâshꞋ | ÷ÉãÆùÑ ÷ÈãÈùÑÄéí / ãÌÀáÄéø |

| Size relative to ÷ÉãÆùÑ | 50x100 | 10x20x20 | 10x10x10 cubit, perfect cube |

| Symbolism of Metals | Bronze | Silver | Fine/pure Gold |

| In éÄùÒÀøÈàÅì | )ùÑåÉîÅø-úÌåÉøÈä =) éÄùÒÀøÈàÅì | ëÌÉäÂðÄéí | äÇëÌÉäÅï äÇâÌÈãåÉì |

| ÷ÉãÆùÑ relative to áÌÆï-àÈãÈí | îÇòÂùÒÆä = îÄöÀååÉú; relative to others, functioning as ëÌÉäÂðÄéí (doing ÷ÄéøåÌá) | ÷ÀäÄìÌÈä & ðÀôÈùÑåÉú îÇîÀìÆëÆú ëÌÉäÂðÄéí (Shᵊm•otꞋ 19.6) | ëÌÇåÌÈðÈä & îÇòÂùÒÆä = îÄöÀååÉú relative to |

| îÄöÀååÉú implemented in | âÌåÌó, e.g., ëÌÇùÑøåÌú, etc. | ðÆôÆùÑ and øåÌçÇ | Enabling |

| Pass Keys(Yᵊsha•yâhꞋu 6.3) | ÷ãåù (#1) | ÷ãåù (#2) | ÷ãåù (#3) |

|

250x161.jpg) |

Near the end of last week's pâ•râsh•âhꞋ, Mosh•ëhꞋ brought down the lukh•otꞋ evidencing the New Bᵊrit (34.27-28). One would think that the New Bᵊrit would begin with a call to tᵊshuv•âhꞋ to obtain ki•purꞋ, to make éÄùÒÀøÈàÅì qâ•

But we are surprised to find the mi•tzᵊw•âhꞋ to keep ùÑÇáÌÈú interposed between the announcement of the New Bᵊrit and the instructions to build the Mi•shᵊkânꞋ. Why?

Last week's pâ•râsh•âhꞋ made clear that only

Thus, this passage conveys a 3-point "Plan of Salvation":

How éÄùÒÀøÈàÅì can obtain ki•

The bᵊrit of ùÑÇáÌÈú is a perpetual testimony attesting that éÄùÒÀøÈàÅì does not do this îÀìÈàëÈä of obtaining ÷ÉãÆùÑ, which only

Only after having realized these can éÄùÒÀøÈàÅì then construct an acceptable medium though which to communicate with

|

35.2 – ùÑÅùÑÆú éÈîÄéí úÌÅòÈùÒÆä îÀìÈàëÈä

|

Among those who have recognized the Biblical truth of keeping ùÑÇáÌÈú, probably the most widespread a•veir•âhꞋ of Tor•âhꞋ is of this related mi•tzᵊw•âhꞋ to do îÀìÈàëÈä the other six days, i.e. to work in an income-earning occupation. Israeli Ultra-Orthodox Kha•reid•imꞋ almost universally defy this mi•tzᵊw•âhꞋ.

|

This logically implies that everyone who aspires to keep ùÑÇáÌÈú is first required to do their utmost to do îÀìÈàëÈä the other six days! îÀìÈàëÈä doesn't do itself and one is commanded even to rest one's animals. (How much more so the "Shabbos goy" invention of arrogant, sanctimonious, racist Jewish supremacists!) Furthermore, this logically implies that everyone who aspires to keep ùÑÇáÌÈú is equally required to do his or her utmost to do îÀìÈàëÈä, an occupation that provides an income. Not only is one required to earn one's living the other six days, it is herein implied that one who keeps Tor•âhꞋ will educate, train, prepare, and apprentice himself or herself in îÀìÈàëÈä so that (s)he will be able to fulfill this mi•tzᵊw•âhꞋ to do îÀìÈàëÈä the other six days.

Shab•âtꞋ is a cessation, an arrest of doing îÀìÈàëÈä. One cannot cease doing îÀìÈàëÈä unless one first does îÀìÈàëÈä. It's impossible to "cease" on Shab•âtꞋ what one hasn't been doing during the week! In other words, whoever doesn't do his or her utmost to do îÀìÈàëÈä for six days isn't keeping Shab•âtꞋ!

In Biblical through Talmudic times, aside from legitimate Ko•han•imꞋ (genealogically documented in the public yo•khas•

The most serious aspect of not engaging in îÀìÈàëÈä the other six days, however, is that it profanes ùÑÇáÌÈú! ùÑÇáÌÈú is defined in this very pâ•suqꞋ' as a cessation of îÀìÈàëÈä! If one hasn't engaged in îÀìÈàëÈä the other six days then one cannot make a cessation of îÀìÈàëÈä; one cannot make ùÑÇáÌÈú. The primary distinction of ùÑÇáÌÈú from îÀìÈàëÈä is lost, thereby profaning ùÑÇáÌÈú!

|

| Preachers & Evangelists usually supported full-time by tithes & offerings (which belong to Tor• |

Religious parasites those who live off of their beggings instead of earning a living that enables them to teach are, by far, most predominant in the Christian world. Not only is the religious parasite undesirable, his (or her) providing the mirage of a seeming outlet for wealthy transgressors to "offer their qor•bân•otꞋ " and "feel" forgiven and saved without having to constrain their lives to Tor•âhꞋ-observance is a far more insidious travesty. It is exactly this kind of vain qor•bânꞋ which

While there are, unfortunately, too many exceptions in the Judaic world (most conspicuously the khareid•imꞋ among whom it is a rarity to work for a living and many are beggars by occupation, even in such places as the Western Wall), the Judaic tradition going back millennia, that religious leaders should earn their own living, still endures. Rather than encourage contributions and donations to support themselves by the effectiveness of their fund-raising techniques and appeals like the Christians do, authentic teachers of Tor•âhꞋ do their best to work in some income-earning occupation to support themselves and their families, thereby enabling them to teach Tor•âhꞋ without becoming a parasite on the community they are supposed to serve. The relationship must be symbiotic like any other productive product or service (i.e. business) in the community, not parasitic. Frequently (especially among the khareid•imꞋ), "valiant wives" support the family in order to free the husband to study and/or teach Tor•âhꞋ.

In contrast to the Christian world, both students and teachers of Tor•âhꞋ regard their roles like any other student, consultant or teacher. A student walking into a college or computer training class expecting the teacher to pay for their tuition and books would be a laughingstock. From the teachers' perspective, teaching requires time, which has a market value since it takes away from the time spent earning a living. Materials and other services cost money which responsible leaders must pay. Likewise, the materials have market value which must counterbalance what the teacher could earn investing his resources, alternately, in his occupational endeavors instead. The idea of aspiring to be, or expecting a religious leader to be, a devoutly religious ascetic or beggar including the many khareid•imꞋ beggars are alien to Judaism. This principle is well established in Tehil•imꞋ 37.23-26.

|

36.5-6—Here, Hebrew isn't the problem; just a widely overlooked aspect of the Judaic Way.

Note how the text differs from the following: "Then they said to Mosh•ëhꞋ, saying 'The kindred are bringing more than enough for the òÂáåÉãÈä of the îÀìÈàëÈä, which

300x199.jpg) |

It seems that Mosh•ëhꞋ understood the principles of defining an objective, budgeting to meet the objective, and disciplined focus—keeping his eye on the ball—which kept success from going to his head. Too many efforts that that begin with benevolent intent achieve a degree of success and then wind up evolving into self-serving idolatry. Mosh•ëhꞋ, having been trained from birth in the vicissitudes of leadership (as a Pharaonic Prince of the world's superpower), based his decisions in Tor•âhꞋ, consistently avoiding becoming a victim of his own success.

When studying the apparel of the Ko•heinꞋ ha-Ja•dolꞋ, both commentators and students have invariably attempted to apply symbolism of the apparel to their own lives. A rethink is in order. Is everyone to identify with the Ko•heinꞋ ha-Ja•dolꞋ? Of course not.

Who, today, are the testifiers, the witnesses, of Tor•âhꞋ and

The answer, of course, is the heart, or

What, in the Beit-ha-Mi•qᵊdâshꞋ, was the box containing the Eid•

One might notice here that just as great ÷ÉãÆùÑ was ascribed to the •ronꞋ ÷ÉãÆùÑ because it was the (only) box (not all boxes) containing the Eid•

Orienting oneself to this revelation opens new vistas in understanding the lessons that the Beit-ha-Mi•qᵊdâshꞋ, by the tav•nitꞋ of Yᵊkhëz•qeilꞋ ha-Nâ•viꞋ, was always intended to teach.

The several partitions and buffers (curtains and walls) between the •ronꞋ ha-QoꞋdësh and outside contaminations becomes obvious. Ha-QoꞋdësh and assimilation are mutually antithetical.

The Ka•porꞋët for the Eid•utꞋ (sometimes referring to the curtain and other times to the cover of the •ronꞋ ha-QoꞋdësh) is etymologically related to Ki•purꞋ.

|

The Miz•beiꞋakh parallels the kâ•sheirꞋ kitchen of the Jew and geir. The Shulkhan (Table) then becomes obvious as the dining table of today's Jew and geir, as does the Lekhem ha-Pan•imꞋ displayed upon it—Tor•âhꞋ shë-bi•khᵊtâvꞋ. The Mᵊnorat ha-Maor, which illuminates, is therefore, by deduction, Tor•âhꞋ shë-bᵊ•alꞋ pëh. The Kiyor (popularly "Laver") clearly parallels the miq•wëhꞋ. Just this brief sketch should give great pause for many to reevaluate Christian notions of deliberately contaminating themselves and rejecting the Tor•âhꞋ ordained by

|

This pâ•râsh•âhꞋ begins:

åÇéÌÇ÷ÀäÅì îÉùÑÆä, àÆú-ëÌÈì-òÂãÇú, áÌÀðÅé-éÄùÒÀøÈàÅì

("Then convoked Mosh•ëhꞋ all of the testifier-witness body of Bᵊn•When I looked in LXX to find the Hellenist (Greek) equivalent of òÅãÈä, I expected to find εκκλησια (ekklæsia; congregation, church) as found in Δευτερονομιον 4:10; 9:10, et al. I shouldn't have been surprised to discover, instead, συναγωγην rendered for Shᵊm•otꞋ 12.3; 35.4, 20; 38.22; et al.

"Synagogue"? In the time of Mosh•ëhꞋ???

Consequently, we shouldn't even carelessly equate the Hellenist term συναγωγην (or its English translation, "synagogue") to (lᵊ-ha•vᵊ

35.2 –

åÌáÇéÌåÉí

äÇùÑÌÀáÄéòÄé,

éÄäÀéÆä

ìÈëÆí

÷ÉãÆùÑ;

ùÑÇáÌÇú

ùÑÇáÌÈúåÉï

ìÇ

And in the seventh day, you shall have a ÷ÉãÆùÑ, a ùÑÇáÌÇú

ùÑÇáÌÈúåÉï to/for

|

Here, as well as in 16.23; 31.15 and wa-Yi•qᵊr•âꞋ 23.3, Tor•âhꞋ explicitly calls the seventh day a ùÑÇáÌÇú ùÑÇáÌÈúåÉï. Tor•âhꞋ also calls both Yom Ki•purꞋ (wa-Yi•qᵊr•âꞋ 16.31 ) and the entire seventh year of Shᵊmit•âhꞋ (wa-Yi•qᵊr•âꞋ 25.4-5) a ùÑÇáÌÇú ùÑÇáÌÈúåÉï (explicitly "ìÈàÈøÆõ," however, not for people).

In wa-Yi•qᵊr•âꞋ 23:24, & 39 the çÇâÌÄéí of Yom

However, it is clear from the Dead Sea Temple Scroll that before the turn of the CE, both Yom

Leading Jewish scholars agree that the Dead Sea Scrolls represent one of the three mainline branches of 1st-century Judaism—and not a fringe extremist group as Christians and earlier scholars have thought.

Consequently, it cannot be logically maintained that there is any significant difference in the strictness in the observance of the seventh day ùÑÇáÌÇú ùÑÇáÌÈúåÉï and the observance of the ùÑÇáÌÇú ùÑÇáÌÈúåÉï of the çÇâÌÄéí.

The question arises as to the meaning of ùÑÇáÌÈúåÉï. The diminutive suffix åï (□on or □un) has been added to the base ùÑÇáÌÈú. But what does it mean? Neither the Soncino English translation of the Tal•mudꞋ nor Ency. Jud. shows any entry in their indices that illuminates this question.

A somewhat circular (petitio principii) discussion of these terms by the Sages (for the instances in wa-Yi•qᵊr•âꞋ) can be found in Artscroll's "Vayikra." At 16.31, ùÑÇáÌÇú

ùÑÇáÌÈúåÉï is explained as "A [ùÑÇáÌÇú] of complete rest. Unlike [çÇâÌÄéí], when the preparation of food and related work is permitted, no labor is permitted on Yom Ki•purꞋ. The [çÇâÌÄéí] are described by the Tor•âhꞋ as ùÑÇáÌÈúåÉï, day of rest (23.1,39), while Yom Ki•purꞋ is called a [ùÑÇáÌÇú] of complete rest." (Artscroll, I11b, 307). Contrary to this assertion, however, we've seen (above) that

At 23.3, the Artscroll editors explain ùÑÇáÌÇú ùÑÇáÌÈúåÉï as "A day of complete rest. [ùÑÇáÌÇú] is not a [çÇâ], per se. It is mentioned with the [çÇâÌÄéí] to teach that anyone who desecrates the [çÇâÌÄéí] is regarded as if he had desecrated the [ùÑÇáÌÇú], and anyone who observes the [çÇâÌÄéí] as if he had observed the [ùÑÇáÌÇú]. The [çÇâÌÄéí], as days of rest, fall under the category of the [ùÑÇáÌÇú], because it is the holiest and the primary day of rest.

|

| Soft |

"There are seven [çÇâÌÄéí] days of rest—two each for [çÇâ ha-Matz•

|

| Ho•sha•nâꞋ Rab•âꞋ |

"[ùÑÇáÌÇú] is mentioned here to differentiate it from the [çÇâÌÄéí] in that all labor, including food preparation, is forbidden on the [ùÑÇáÌÇú]. Even if a [çÇâ] falls on a [ùÑÇáÌÇú], it is forbidden to do such labor (Ramban)." (ibid. p. 395).

Clearly, there are fallacies in the speculations above.

In connection with the seventh day ùÑÇáÌÇú ùÑÇáÌÈúåÉï at 23.3, Tor•âhꞋ goes on (23.7-8, 21, 25, 35-36; see also bᵊ-Mi•dᵊbarꞋ 28.18, 25-26; 29.1, 12, 35) to prohibit ëÌÈì îÀìÆàëÆú òÂáÉãÈä .

Artscroll editors say of îÀìÆàëÆú òÂáÉãÈä: "Laborious work." No English translation captures the sense of the term. According to Rashi (v. 8), it means work that one regards as a necessity: 'even essential work that will cause a significant loss if it is not performed' " (ibid.).

300x198.jpg) |

Since the Tor•âhꞋ emphasizes that such work may not be done on the first and seventh days of the festival, the implication is that such work is permitted on the Intermediate Days. Thus, on the Intermediate Days, only such work is permitted as would cause a loss if it were to be delayed. "According to Ramban, the term means work that is a burden, such as ordinary labor in factory and field. Only such work is forbidden on [çÇâÌÄéí], but 'pleasurable work,' i.e., preparation of food, is permitted. [Ask the better half about that definition].

"Whatever the interpretation of this term, all agree that the preparation of food, including such labors as slaughter and cooking, is permitted on [çÇâÌÄéí] that fall on weekdays." (ibid. 396).

It seems to me that slaughter and cooking, if reasonably viable, should be done before any ùÑÇáÌÈúåÉï, to observe it as a ùÑÇáÌÇú as closely as practicable. Despite the allowance by many commentators, Nᵊtzâr•imꞋ should not do îÀìÈàëÈä on any ùÑÇáÌÈúåÉï.

Finally, at 23.24, Artscroll describes ùÑÇáÌÈúåÉï (used alone): "A rest day: The Sages expound that this word refers to all the [çÇâÌÄéí], and has the status of a positive commandment, enjoining rest on the holy days. It has the connotation that one must avoid even excessive labor that is not a forbidden labor. For example, for one to rearrange his furniture on a [çÇâ] is not technically a forbidden labor, but it is surely a failure to rest (Ramban)." (ibid. 403). By contrast, the Nᵊtzâr•

Under "Hebrew Grammar, Morphology, Noun Fonnation, 9. Suffixes" Ency. Jud. offers for the suffix åï (on): "Its modern use is pre-eminent 1) to create diminutives, 2) to indicate publications which appear at regular intervals, and lists of similar items. But there are other nouns derived in this way and the formative fulfills other functions." (8.114).

Assuming, at some risk, that the modern usage has roots in ancient usage rather than being a complete innovation, we might eliminate the diminutive usage since diminutives are hardly used in tandem with their original counterpart. I.e., diminutive usage wouldn't seem to explain the doublet phrase ùÑÇáÌÇú ùÑÇáÌÈúåÉï.

There is no mention of ùÑÇáÌÈúåÉï in the indices to the Pseudepigrapha in either the Charles' or Charlesworth's editions.

Orion (Dead Sea Scroll internet forum) scholars advise me that their indices of the Dead Sea Scrolls show that the Temple Scroll instances already cited are the only known occurrences of the term.

|

There is, however, a basis in The Nᵊtzârim Reconstruction of Hebrew Matitᵊyâhu (NHM, in English)![]() 28.1 for associating ùÑÇáÌÈúåÉï with the connotation of a group or set of similar items: "On Mo•tzâ•

28.1 for associating ùÑÇáÌÈúåÉï with the connotation of a group or set of similar items: "On Mo•tzâ•

Here, the two ùÑÇáÌÈúåÉï of çÇâ ha-Matz•

Christian scholars dismissed σαββατων here as an anomalous singular form constructed from the perceived plural σαββατα, being anyway inexplicable Aramaic (cf. Vine's Expository Dictionary of NT Words: "the plural form was transliterated from the Aramaic word, which was mistaken for a plural; hence the singular, sabbaton, was formed from it"; p. 983).

It turns out from this Christian error that many Διαθηκη Καινη (NT) instances of questions arising about "the sabbath" may have related, instead, to a ùÑÇáÌÈúåÉï. All of the instances in the Διαθηκη Καινη (NT) are considered declensions of σαββατων (cf. The Englishman's Greek Concordance of the NT, p. 679).

Together, the evidence suggests that ùÑÇáÌÈúåÉï is the superset of which each instance of ùÑÇáÌÇú is a member. In fact, the English "Shabat of the Shabaton" is a perfect translation of "ùÑÇáÌÇú ùÑÇáÌÈúåÉï". It then follows that îÀìÈàëÈä is prohibited on any ùÑÇáÌÇú of the ùÑÇáÌÈúåÉï.

|

35:1— The English, "Mosh•ëhꞋ gathered all of the congregation of Bᵊn•eiꞋ éÄùÒÀøÈàÅì," doesn't do justice to the implications inherent in the Hebrew.

Influenced by NT English, all English translations gloss over the òÅã family of Hebrew terms.

|

òÅã refers to a witness in a court of law, an eyewitness. Reflect, in this light, on Shᵊm•otꞋ 20.16; 22.12; 23.1; Yᵊsha•yâhꞋu 43.9, 10, 12; 44.8-9 & Mi•shᵊl•eiꞋ Shᵊlom•ohꞋ 19.28: "A witness of Bᵊli•ya•

The fem. form of this noun, òÅãÈä, describes either a single witness in the feminine gender or a group of eye-witnesses. To see the difference in connotation, substitute "eye-witness-group" for "congregation" in Shᵊm•otꞋ 12.3, 6, 19, 47 et al.).

òÅãåÌú refers to the testimony of an inanimate witness, i.e., hard evidence. To appreciate the effect of this verb, substitute "hard evidence" for testimony in Shᵊm•otꞋ 16.34; 26.16, 21, 22; 26.33, 34; et al.).

òÅãåÌú contrasts with ÷äì and ÷äéìä. "Gathered," in Shᵊm•otꞋ 35.1 should be rendered convoked, perhaps even subpoenaed. "Congregate" is even an understatement.

In this light, the English of this pâ•suqꞋ more accurately reads "Then Mosh•ëhꞋ convoked the entirety of the group-of-eyewitnesses [to the revelation of Tor•âhꞋ at Har Sin•aiꞋ] of Bᵊn•eiꞋ éÄùÒÀøÈàÅì'"

|

This pâ•râsh•

Most of the other communities in Orthodox Judaism differentiate between observance required on Yâm•imꞋ Tov•imꞋ of the çÇâÌÄéí and that of ùÑÇáÌÈú. According to the other communities, when a Yom Tov precedes a ùÑÇáÌÈú, for example, they permit certain cooking on the yom tov. For them, a lower level of observance is required for Yâm•imꞋ Tov•imꞋ of the çÇâÌÄéí than for the weekly ùÑÇáÌÈú. The reasoning usually given is that the Yom Tov is only a "ùÑÇáÌÈúåÉï" while ùÑÇáÌÈú is ùÑÇáÌÈú.

However, 35.2 defines ùÑÇáÌÈú as a ÷ÉãÆùÑ; ùÑÇáÌÇú ùÑÇáÌÈúåÉï. The connective form of ùÑÇáÌÈú (contrast with—carefully—with the regular noun form: ùÑÇáÌÈú) dictates reading this as "a ùÑÇáÌÈú of ùÑÇáÌÈúåÉï. Therefore, ùÑÇáÌÈúåÉï is equivalent to ùÑÇáÌÈú-observance; not any different observance – and certainly cannot refer to a laxer observance, because it also applies to the weekly ùÑÇáÌÈú as well!

The Nᵊtzâr•imꞋ position on this issue is more strict than any of the other Jewish communities: Yâm•imꞋ Tov•imꞋ of the çÇâÌÄéí are special Shabât•

Beside commanding that we work six days (a too-often neglected aspect of the mi•tzᵊw•âhꞋ), ëÌÈì-äÈòÉùÒÆä

áåÉ

îÀìÈàëÈä

éåÌîÈú: xlation While ignored by most modern Jews, and loudly exaggerated by misojudaics, Bat•eiꞋ-Din through the centuries have consistently understood "éåÌîÈú" here to mean excision from Am éÄùÒÀøÈàÅì. This is well-documented in Tal•

MiꞋshᵊnâh : "a Sanhedrin that kills once in 7 years is called "çåÉáÀìÈðÄéú." R. Eleazer Bën Azariah said: once in 70 years. R. Tarpon and R. Aqiva said: Were we members of a Sanhedrin, no person would ever be executed. Rabban Shimon Ben-Gamalieil remarked [if the opinion of R. Tarpon and R. Aqiva were adopted], "they would encourage the proliferation of murderers in Israel." …Gᵊmâr•

âꞋ : (a Sanhedrin that kills, etc.) "The question was raised whether the comment [of R. Eleazer Bën Azariah was a censure, namely] that even one execution in 70 years branded the Sanhedrin as "çåÉáÀìÈðÄéú", or [a mere observation] that [an execution] ordinarily happened but once in 70 years? – It remains [undecided]." (Ma•sëkꞋ ët Mak•otꞋ 1.10; 7a; Soncino and ou.org).

|

| Logic NOR gate (not philosophy calling itself "logic") |

Imposing an artificial dilemma is a favorite fallacy of pseudo-logicians, shutting out any other alternatives that might threaten their conclusions. In this case, the statement by R. Eleazer Bën Azariah was neither censure nor mere observation (the imposed artificial dilemma) but, certainly, wishful hyperbole, while those of R. Tarpon and R. Aqiva seem to echo the voices one hears today from liberals who have lost touch with the real world, the presence in it of those who willfully perpetrate injustice and hurt, and the Tor•

In an earlier si•dᵊr

|

35.3 shows why one should never rely on any English translation.

250x376.jpg) |

Let's start with the English of a comparatively good translation: The Koren Jerusalem T"nakh.: "You shall kindle no fire" (throughout your habitations on the sabbath day). The Artscroll Stone Edition follows the same idea, reading: "You shall not kindle fire."

Now reverse translate that, to Hebrew: ìÉà úÄÌ÷ÀãÀÌçåÌ àÅùÑ. According to Klein's, this verb, ÷ÈãÇç, is the verb that "orig. meant 'to make fire by rubbing.' " (Point of information: In Modern Hebrew, this verb refers to having a fever.)

However, this is not how Tor•âhꞋ reads!

Tor•âhꞋ reads: ìÉà úÀáÇòÂøåÌ àÅùÑ, you shall not prepare and assemble kindling and wood to make a fire and ignite it!

Today, in Modern Hebrew, áÌÄòÅø means simply to kindle or light a fire. In ancient times, áÌÄòÅø included the preparation of the fire after the kindling had been gathered: preparation of the oven or fire place, along with the actual ignition or lighting of the fire. Even when out camping today, "Kindle (or make) a fire" (from scratch, as opposed to simply igniting a prepared fire) carries much the same connotation.

|

This is why (bᵊ-Mi•dᵊ

This also relates to the contribution of the man of the house in preparing the ùÑÇáÌÈú candles for the woman to light. In preparing the candles, the man has contributed to the áÌÄòÅø àÅùÑ preparation preceding ùÑÇáÌÈú lights!

Why did

|

Tradition holds that kindling fire is an act of creation, and acts of creation are what are prohibited on ùÑÇáÌÈú, in commemoration of

However, the very notion that man "creates" anything at all—perhaps excepting an idea or thought, and that is debatable—conflicts with science and logic' and is arrogantly mistaken. Only

If there is anything at all that we do that could conceivably be regarded as genuinely creative it would be our abstract ideas. Therefore, if there is any relationship between creativity and work prohibited on ùÑÇáÌÈú, then thinking is the one activity that would be prohibited on ùÑÇáÌÈú! However, Orthodox Ha•lâkh•âhꞋ doesn't prohibit thinking,—it doesn't even prohibit thinking or mental planning about business, financial and other occupational-work matters—on ùÑÇáÌÈú. It is thereby proven (reductio ad absurdum; i.e. proof by disproof) that creativity cannot be prohibited on ùÑÇáÌÈú!!!

Philosophers argue that even our ideas are merely reworkings of previous ideas, and not truly creative. Science also confirms that fire is basically the visible manifestation of oxidation (not related to electricity), not a creation.

The only viable remaining reason for prohibiting áÌÄòÅø àÅùÑ on ùÑÇáÌÈú is to prohibit the work involved in this activity that should be relegated to the profane days, despite the obvious need to eat and keep warm on ùÑÇáÌÈú. The work must be done in the profane days.

|

![]()

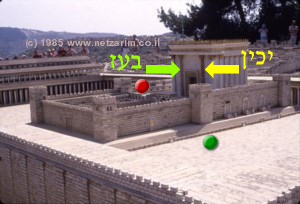

éÈëÄéï áÌÉòÇæ — 7.21

|

| Beneath the red dot:: Located on the balcony at the SE corner of the inner court of the Beit ha-Miq•dâshꞋ ha-Shein•iꞋ, the Beit Din hâ-Jâ•dolꞋ, which supervised all of the lesser Bât•eiꞋ-Din throughout the land, convened in the Chamber of Hewn Stone.

Green dot: ñÉøÈâ – 1.5m high stone lattice preventing goy•imꞋ from approaching any closer. See also diagrams in the Suk•âhꞋ ÂlꞋëph page of our Museum. Photographed © 1985 by Yi•rᵊmᵊyâhꞋu Bën-Dâ•widꞋ at the Holyland Model site, Yᵊru•shâ•laꞋyim |

These two pillars, with their names, symbolize what ShᵊlomꞋoh ha-mëꞋlëkh intended the Beit-ha-Mi•qᵊdâshꞋ to represent.

áòæ (Bo•az) is a combination of áå (bo; in it/him) and òæ (az; strength); i.e., in him (or it) is strength.

éëéï (Yâkhin) is much more complex in meaning. The meaning incorporates three interlocked themes: correct-directed readiness. The root verb is ëåï (this pa•alꞋ root form is never used, so no pronunciation is correct).

In the niph•alꞋ, ðëåï (nakhon) means "to make ready"; but this is also the word for "right" in the sense of "correct." ("Right," in contrast to "left," is an entirely unrelated word.)

The participle of the huph•alꞋ, îåëï (mukhan) means "ready."

The verbal noun of the pi•eilꞋ, ëååï (kiwun) means direction, course or aim; and another cognate, ëååðä (kawanah), means intention or meaning.

All of these ëååðåú (kawanot; meanings) were inherent in these two pillars.

|

![]()

| Tor•âhꞋ | Translation | Mid•râshꞋ RibꞋi Yᵊho•shuꞋa: NHM |

NHM |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||

|

![]()

The Table of Gradations (2005 Torah section) shows that ëååðä equates to øåç; the former associated with îÇòÂùÒÆä = îÄöÀååÉú relative to

•marꞋ RibꞋi Yᵊho•shuꞋa: "Therefore, I've told you, for every misstep, and madness, and derisive-slander, ki•purꞋ may be obtained for man. However, no ki•purꞋ shall be made for the derisive-slanderer of the øåç'" (NHM![]() 12.31).

12.31).

|

![]()

ha-Eil, may He be blessed, gave man a mouth so that he could train it [the mouth] in the Dᵊvâr•imꞋ, which benefit the body and nëphꞋësh.

Bless Him for all the Dᵊvâr•imꞋ that are enjoyed in this world-age and pray before His Face and request of Him khësꞋëd, and ingratiate yourself before His Face in everything that is necessary for [khësꞋëd] with a complete and afflicted heart and He will hearken to you. As it is written, "Close is

And if [a person] succeeds to ascend to the supreme height—to study Tor•âhꞋ, to teach it, to exlain it and to instruct it to the perplexed; in praising the oratory of Dᵊvâr•imꞋ [their] good measures and to denounce deprecatory-speech [before] them—[then] A•shᵊr•eiꞋ to him, and A•shᵊr•eiꞋ to his portion; that he gains, and causes others to gain. All of them will be called his sons and the Ma•as•ëhꞋ of his hands.

However, the mouth that was created for this, it was more than enough to warn man that he shouldn't engage it in idle chatter; for the day is short, the work is great and man has no days to lose in prattlings. Even more so, it wasn't necessary to warn man not to utter prohibited or loathsome speech; dâ•vârꞋ, for even a beast prefers good and loathes bad in what it can achieve.

And it was more worthy to do this for the man who has a mind, which his Creator gave him to choose the good and to loath the râ, [the mind] which he had to sanctify his mouth and to separate it from Dᵊvâr•imꞋ of nonsense and even more so prohibited Dᵊvâr•imꞋ. In the mouth that was created in a qâ•

The first Kha•sid•imꞋ made themselves like the ministering [lit. "serving"] ma•lâkh•imꞋ and their mouths as a serving vessel, which is not used for khol things except when they necessarily had to deal with them for their bodies.

It is memorized in Gᵊmâr•âꞋ di-Vᵊnei Ma•arâvâ: All speech is bad, only those [discussions] about Tor•âhꞋ are good. All investigations [lit. plowings] are bad, only investigations [lit. plowings] of Tor•âhꞋ are good.

When the ancient ones saw the opinions of people, how weak they are, and their tongue, which is created to speak wisely, [they saw that] it wasn't enough for [people] to use [their tongue] for vain Dᵊvâr•imꞋ. Their [mouths] were also agape in things that were â•surꞋ. Even though [the mouth] is soft and enclosed by two fences, men sharpen it as a sharp arrow and speak great things with it. They have reproved with a speech, as it is memorized in Masekhet Arâkhin, chapter Yeish ba-Arâkhin (16b): RabꞋi Yo•khân•ânꞋ said on behalf of RabꞋi Yosei ben Zimrâ: what is it that is written: "What will a tongue of deceitfulness give you and what will it add" [i.e. what other guard can I put on you to stop deceit, etc.] (Tᵊhil•imꞋ 120.3)? ha-Qâ•doshꞋ, Bâ•rukhꞋ Hu, said to the tongue: All the organs of a man are [held-together] upright, but you are hurled [out]. All the organs of a man are on the outside but you are on the inside. Moreover, I've even surrounded you by two fences, one of bone and one of flesh. [Despite this,] "What will a tongue…?"

It is memorized in Mi•dᵊrâshꞋ ha-ShᵊkhëmꞋ. RabꞋi Elâzâr on behalf of RabꞋi Yosei ben Zimrâ: A man has 248 organs. From them, there are those that are upright and those that are prone. But a tongue is placed between two cheeks with a water duct below, which is periodically reproduced. [Despite the water,] come and see how many fires it burns. If [the tongue] were upright and standing, [it would burn] even the more so.

Our Rabbis talked a little about this, of the evils that circle their nᵊphâsh•otꞋ when they gape their mouth [in situations that] are not worthy. For those who revere [

They also spoke upon other topics that come to a person concerning every single saying for which warnings were given; as they are written in every single principle of this oil-lamp [of Mᵊnor•atꞋ ha-Mâ•orꞋ by Yitz•khâqꞋ Ab•u•havꞋ.

|

|